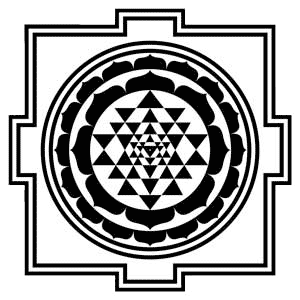

On 18-June-2004, a 6.5-foot statue of dancing Siva was unveiled at CERN by its Director General, Dr. Robert Aymar. A special plaque next to the statue explained the traditional symbolism of Siva’s dance also quoted Fritjof Capra a particle physicist himself, ‘For the modern physicists, then, Shiva’s dance is the dance of subatomic matter.’ The statue, a gift from the Indian Government, was to commemorate the long association of Indian scientists with CERN that dated back to 1960s.

Fritjof Capra became a well-known name among ‘New Age’ aficionados as well as serious thinkers (not necessarily mutually exclusive groups) in the 1970s. His fame in India has been largely through the way he integrated the image of dancing Siva with the dynamic nature of sub-atomic particles. Capra wrote quoting Ananda Coomaraswamy (edited by Zimmer) in his cult classic 'Tao of Physics':

For the modern physicists, then, Shiva’s dance is the dance of subatomic matter. As in Hindu mythology, it is a continual dance of creation and destruction involving the whole cosmos; the basis of all existence and of all natural phenomena. Hundreds of years ago, Indian artists created visual images of dancing Shivas in a beautiful series of bronzes. In our time, physicists have used the most advanced technology to portray the patterns of the cosmic dance. The bubblechamber photographs of interacting particles, which bear testimony to the continual rhythm of creation and destruction in the universe, are visual images of the dance of Shiva equalling those of the Indian artists in beauty and profound significance. The metaphor of the cosmic dance thus unifies ancient mythology, religious art, and modern physics. It is indeed, as Coomaraswamy has said, ‘poetry, but none the less science’ (The Tao of Physics, p. 272).

It was the powerful way in which the physicist–author wrote about the parallels between the dancing Deity and the web of relations emanating and dissolving in the realm of sub-atomic particles that ultimately led to the establishment of a Siva statue at CERN.

THE DANCING SIVA

For Hindus who had been constantly abused as worshippers of barbarous grotesque deities, the book and its imagery came as a sort of scientific vindication of ancient wisdom.

How the ‘Tao of Physics’ actually affected the psyche of educated Hindus is in itself an interesting phenomenon. Just a few years before its publication, Dravidian racists had put up a poster which showed the very cosmic dance as nonsensical superstition with American astronomers putting their feet right on the crescent moon adorning the dancing Siva – thus Siva was under the feet of the American astronaut. For Hindus who had been constantly abused as worshippers of barbarous grotesque deities, the book and its imagery came as a sort of scientific vindication of ancient wisdom. Interestingly, while Capra saw the symbolism of Siva’s cosmic dance in the sub-atomic particle trajectories captured in the bubble chamber, the famous chemist, Illya Prigogine who was best known for his concept of dissipative structures, had used the dance of Siva to symbolize the thermodynamic ‘theory of structure, stability and fluctuations.’ Siva’s cosmic dance, even as a metaphor, thus pervaded both the sub-atomic and molecular levels of reality. At the opposite end of the spectrum, Carl Sagan saw in the cyclic cosmic dance of Siva ‘a kind of premonition of modern astronomical ideas’ like the oscillating universe. More recently Dr. V. S. Ramachandran, the modern cartographer of the dynamic brain, used the metaphor of the dance of Siva in an existential sense: “If you are really part of the great cosmic dance of Shiva, other than a mere spectator, then your inevitable death should be seen as a joyous reunion with nature rather than a tragedy.” One wonders if there is another spiritual/ artistic/mythological symbol like that of the dancing Siva that humanity has created which can accompany our own understanding of the universe, inner and outer!

Unfortunately, the interest mostly stopped right there. In 1982, Fritjof Capra delivered a series of lectures at Bombay University, arranged by University Grants Commission of India that accompanied the publication of his next book, ‘The Turning Point.’ In the lecture series, the physicist enlarged upon his vision and spoke of a systems view of life. Interestingly among the Hindu circles, the founder of the trade union with Indic ideology BMS (Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh: Association of Indic workers), Dattopant Thengadi alone seemed to have been aware of the importance and relevance of Capra’s expansive vision in relation to their ideology – particularly in the larger context of ‘Integral humanism,’ an ideology advocated by Jan Sangh (a party perceived as rightwing, though such categories do not accurately apply to Indian politics) ideologue Deendayal Upadhyaya.

PARADIGM SHIFT

In ‘The Turning Point’ (1982), Capra explored how the changed vision of nature emanating from the ‘new physics’ also changes the way we look at life, our psychology, society, politics, economics, and environment. He identified the interconnectedness that the theoretical physicists like David Bohm were talking about in such a powerfully poetic language as having an impact on the way other disciplines viewed and approached their own subject matter. In general, a ‘paradigm shift’ has been happening, he claimed, from the Newtonian-Cartesian essentially mechanistic vision of the universe to a more holistic, interconnected, organic vision of universe.

From a reductionist mechanical view of life, we are moving towards a systems view of life. From Freudian and behaviorist models in psychology, we are moving towards the more holistic and humanistic approaches to the psyche propounded by Maslow and Jung. In economics, Capra also identified a shift as reflected in the ‘Buddhist economics’ of E. F. Schumacher. His book explored all these developments in detail.

Here Capra takes a sympathetic view of Marx that would later become central to ecological movements throughout the world.

Here Capra takes a sympathetic view of Marx that would later become central to ecological movements throughout the world. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many Marxist activists as well as scholars have shifted their focus to an ecological critique of capitalism. Capra does see Marx as a sort of pioneering holistic thinker far ahead of his times:

Many of these experiments were very successful for a while, but all of them ultimately failed, unable to survive in a hostile economic environment. Karl Marx, who owed much to the imagination of the Utopians, believed that their communities could not last, since they had not emerged "organically" from the existing stage of material economic development. From the perspective of the 1980s, it seems that Marx may well have been right (The Turning Point, p. 203).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, many Marxist activists as well as scholars have shifted their focus to an ecological critique of capitalism

In Capra’s assessment, Marx comes out as a pioneering, organic process-philosopher studying social dynamics:

Marx's view of the role of nature in the process of production was part of his organic perception of reality, as Michael Harrington has emphasized in his persuasive reassessment of Marxian thought. This organic, or systems view is often overlooked by Marx's critics, who claim that his theories are exclusively deterministic and materialistic (The Turning Point, p. 207).

However, Capra makes it clear how he differs from Marx:

The Marxist view of cultural dynamics, being based 'On the Hegelian notion of recurrent rhythmic change, is not unlike the models of Toynbee, Sorokin, and the I Ching in that respect. However, it differs significantly from those models is in its emphasis on conflict and struggle. ... Therefore, following the philosophy of the I Ching rather than the Marxist view, I believe that conflict should be minimized in times of social transition, (The Turning Point, p. 34-35).

In terms of the history of political ecology, others differ from Capra’s assessment of Marx. As economist Joan Martinez-Alier points out, the neglect of ecology has been inherent in Marxism from the very beginning as seen in the rejection of the work of Sergi Podolinsky by Marx and Engels. Podolinsky, an Ukrainian physician and socialist, tried to integrate other issues with the theory of value of the laws of thermodynamics – particularly the second law. Martinez-Alier points out that Podolinsky had analyzed the energetic of life and had applied it to the dynamics of economic system. Podolinsky had argued that the human labor “had the virtue of retarding the dissipation of energy, achieving this primarily by agriculture, although the work of a tailor, a shoemaker or a builder would also qualify, as productive work, affording 'protection against the dissipation of energy into space,'“ (Martinez-Alier, Energy, Economy and Poverty: The Past and Present Debate, 2009, p. 40).

TOWARDS ECO-FEMINISM

The Turning Point also reveals a growing influence of eco-feminists on Capra like Charlene Spretnak, Adrienne Rich, and Hazel Henderson.

Spertnak seems to advocate the indigenous Goddess tradition of Marija Gimbutas, according to which the Kurgan people descending from the steppes brought with them patriarchy and sky gods and destroyed the earth-goddess tradition then prevalent throughout Europe.

Particularly important is Charlene Spretnak, an eco-feminist. Capra coauthored with Spretnak ‘Green Politics,’ subtitled ‘Global Promise’ (1984). The book projects Green politics as an alternative politics emerging from the new vision of reality. In 1983, 27 parliamentarians elected in West Germany belonged to Green Party – a new phenomenon then. Capra and Spretnak saw this as the Greens transcending ‘the linear span of left-to-right.’ The Marxist influence was very much visible. What was even more visible was the way Marxists within the Greens were out of sync with the cardinal principles of the holistic Greens. Capra and Spretnak record:

We began to perceive friction between the radical-left Greens and the majority of the party as we travelled around West Germany and asked our interviewees whether a particular goal or strategy they had described was embraced by everyone in this heterogeneous party: ... 'Does everyone in the Greens support nonviolence absolutely?' we asked. 'Yes... except the Marxist-oriented Greens.' 'Does everyone in the Greens see the need for the new kind of science and technology you have outlined?' 'Yes ... except the Marxistoriented Greens. 'Does everyone in the Greens agree that your economic focus should be small-scale, worker-owned business?' 'Yes ... except the Marxist-oriented Greens.' (pp. 20-1)

Spertnak seems to advocate the indigenous Goddess tradition of Marija Gimbutas, according to which the Kurgan people descending from the steppes brought with them patriarchy and sky gods and destroyed the earth-goddess tradition then prevalent throughout Europe. Spertnak herself had written a book on the lost goddesses of early Greece. This of course is the ‘Aryan invasion Theory’ of Europe that was later relegated to the sidelines of the academic stream in the West. Marxist historian and polymath D. D. Kosambi had attempted a similar model for ancient Indian history.

DISCOVERING THE DYNAMIC UNIVERSE

Heisenberg was intrigued when Capra showed how ‘the principal Sanskrit terms used in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy - brahman, rta, lila, karma, samsara, etc. - had dynamic connotations’ (p. 49).

Capra’s next important book, (‘Uncommon Wisdom,’ 1986), was about his encounters with the remarkable personalities who shaped his worldview. In some way, this book is an autobiographical account of the evolution of his worldview. It was in this book that Capra documents Heisenberg being ‘influenced, at least at the subconscious level, by Indian philosophy’ (p. 43). During his second visit to Heisenberg, Capra shows the venerable old man of physics the manuscript of ‘Tao of Physics’. To Capra the ‘two basic themes running through all the theories of modern physics, which were also the two basic themes of all mystical traditions’ are the ‘fundamental interrelatedness and interdependence of all phenomena and the intrinsically dynamic nature of reality.’

Interestingly Heisenberg, while agreeing with Capra on his interpretation of physics, states that though he was ‘well aware of the emphasis on interconnectedness in Eastern thought.

Even the great minds like Heisenberg, while not unaware of the depth of Indian culture and philosophy, were still susceptible to the stereotype of a passive, fatalistic, mystic India

However, he had been unaware of the dynamic aspect of the Eastern world view.’ Heisenberg was intrigued when Capra showed how ‘the principal Sanskrit terms used in Hindu and Buddhist philosophy - brahman, rta, lila, karma, samsara, etc. - had dynamic connotations’ (p. 49). Even the great minds like Heisenberg, while not unaware of the depth of Indian culture and philosophy, were still susceptible to the stereotype of a passive, fatalistic, mystic India. It is interesting to note that Capra could find dynamism in the terms, especially Karma, for the term has been singled out in academia for stereotyping Indian culture as fatalistic. There is also the encounter with Geoffrey Chew – the physicist who pioneered the S-Matrix theory that today survives largely in string theory. He also recounts how he was shocked to find parallels between his own formulation and the philosophical vision of ancient Buddhists (particularly Mahayana school) when his son in senior high school pointed it out to him (p. 53). Comparing David Bohm, another cult-physicist who also looked for a deeper order under the quantum realm, Capra emphasizes the influence of J. Krishnamurthy on both David Bohm and Capra himself.

The book wades through the thoughts of anthropologist and cyberneticist Gregory Bateson, whose emphasis was on the connections and circularity of cause-effect relations, particularly in biological systems.

Capra also details his interactions with psychiatrists R. D. Laing and Stanislav Grof. To Capra they signified a shift from Freudian psychology, while sharing a deep interest in Eastern spirituality and a fascination with ‘transpersonal’ levels of consciousness.

To Capra, Chi is ‘a very subtle way to describe the various patterns of flow and fluctuation in the human organism’ (p. 160).

In medicine, he emphasizes holistic medicine. When he talks of the Eastern medical systems, it is Chinese medicine and Chi that get mentioned. It is through Margaret Lock, a medical anthropologist, that the physicist gets his knowledge of the Eastern medical system. To Capra, Chi is ‘a very subtle way to describe the various patterns of flow and fluctuation in the human organism’ (p. 160). What he says for Chi can also apply to Prana as well, and this framework allows those who synthesize Indian knowledge systems with modern science escape the Aristotelian/Cartesian binary trap of vitalism. Another very important person in the book is Hazel Henderson, the author of ‘Creating Alternative Futures.’ Often described as an iconoclastic economist and futurist, one important aspect of Henderson’s thinking is, according to Capra, her prediction that ‘energy, so essential to all industrial processes, will become one of the most important variables for measuring economic activities’ (p. 236). Here again she has been anticipated by Podoloinsky. Henderson today champions the cause of what she calls ethical markets.

What he says for Chi can also apply to Prana as well, and this framework allows those who synthesize Indian knowledge systems with modern science escape the Aristotelian/ Cartesian binary trap of vitalism.

Belonging to the Universe’ (1991) is a dialogue between Capra, and David Steindl-Rast, a Benedictine monk. Thomas Matus, another Catholic theologian, was also present during this exchange. Here Capra reveals how he turned away from Catholicism, the religion of his birth, and ' found very striking parallels between the theories of modern science, particularly physics [which is Capra’s field], and the basic ideas in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism.' Then he reconnects with the religion of his birth through David Steindl-Rast. Here one sees how Capra, a lapsed Catholic now returning with an acquired Eastern heritage, struggles to belong to a common human spiritual heritage. He says: "Now Juliette (his daughter) is two, and soon she'll be at the age of stories.

I want to tell her tales from the Mahabharata

and the other Indian stories, the Buddhist stories, and some of the Chinese stories. But I certainly also want to tell her Christian and Jewish and Western stories of our spiritual tradition and Sufi stories, too" (p. 4).

However, there are problem areas. For an Indian reading this conversation, he might find how amazingly Capra’s questions reflect his own, and some of the answers that Steindl-Rast gives are elusive and not exactly what one can call honest (For an example, see pages 78-9). In hindsight, Capra might not have known then, but both Matus and Steindl-Rast would have known for sure, that Mother Teresa was definitely engaging in conversion activity and that, more often than not, the native spiritual traditions were branded by missionaries as agents of ‘oppression, exploitation, human misery,’ with secular terms that are the equivalent of ‘Satan’ and ‘Devil’ of the bygone medieval and even early colonial ages, when inquisition was openly called Inquisition.

Nevertheless this book is important for Hindu scholars who want to study and have dialogue with Christianity. It reveals the inner churning happening in the Christian psyche - not at the institutional level perhaps but at the individual level. If Hindus want to have a global Dharmic network as they often imagine, then they have to seriously look for networking nodes in such spaces. Capra also provides an insight into how Christianity created a new narrative of its missionary activities – which remain almost the same as it was during the colonial times, yet couched in a new language that even the admirers of Eastern systems in the West would accept.

In EcoManagement (coauthored with Ernest Callenbach, Lenore Goldman, Rudiger Lutz and Sandra Marburg, 1993), Capra proposed ‘a conceptual and practical framework for ecologically conscious management.’ In 1995, he co-edited a collection of essays with Gunter Pauli, an eco-entrepreneur, (Steering Business toward Sustainability), with essays by likeminded people in economics, business management, and ecology, trying to chart a practical model for sustainable development through private enterprise.

LIFE AS COGNITION: A NEW SYNTHESIS

‘The Web of Life’ (1996) is equally as important as the ‘Tao of Physics.’ It was a great integration of evolution, ecology, and cybernetics. It was a veritable manifesto of systems biology directed towards the common man as well as the professional biologist who lived compartmentalized lives. The book explains in great detail how the paradigm shift much discussed in physics with the emergence of now a century-old new physics, has also been happening in biology. The concept of biosphere formulated by Edward Suess at the end of nineteenth century was developed by Russian geo-chemist Vernadsky. His conception of biosphere comes closest to the Gaia theory–earth as an evolving living system independently arrived at by James Lovelock, a bio-physicist, and Lynn Margulis, the microbiologist who also proposed symbiogenesis which was opposed fiercely by orthodox Darwinians but eventually accepted by mainstream biology today. The book conceptualizes evolution more as a cooperative dance rather than a struggle for existence. At another level the book looks at life fundamentally as a process of cognition. This view of life is based on the path-breaking work of two Chilean scientists, Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela.

The concept of biosphere formulated by Edward Suess at the end of nineteenth century was developed by Russian geo-chemist Vernadsky. His conception of biosphere comes closest to the Gaia theory–earth as an evolving living system independently arrived at by James Lovelock, a bio-physicist, and Lynn Margulis

Influenced by Buddhist epistemology, these two biologists see cognition as not representing ‘an external reality, but rather specify one through the nervous system's process of circular organization.’ Capra quotes Maturana’s decisive statement with agreement: “Living systems are cognitive systems, and living as a process is a process of cognition. This statement is valid for all organisms, with and without a nervous system.” (pp. 96-97).

Another important view of biological systems developed by Maturana & Varela team is autopoiesis. Capra points out from the original paper of Maturana & Varela that this model enquires not into the 'properties of components,' but studies the 'processes and relations between processes realized through components.' One cannot miss the overtone of Alfred North Whitehead’s process view of consciousness here. In Indian culture the autopoiesis is celebrated as Divine and we have a name for it – Swayambu. Most of the Lingams today enshrined in the grand splendor of stone temples are Swayambu. So are many of the roadside deities under the trees. In South India a self-evolved termite mound is venerated as a living manifestation of Divine Feminine. Autopoiesis can be traced to the non-linear dynamics of Illya Prigogine’s dissipative structures. And curiously, he like Capra had used Siva’s dance as a metaphor for the basic process of the realm he studied – the molecular dynamics of chemical systems. The book is a veritable odyssey into the billion years of evolution of the phenomenon of life at the planetary level and lays the foundation for the future work of Capra.

DISCOVERING THE NETWORKS

The next book 'The Hidden Connections' (2002), as the subtitle of the book suggests, aims to integrate the ‘'the biological, cognitive and social dimensions of life into a science of sustainability'. It speaks of networking at the social level based on the views of life he had presented in his ‘Web of Life’. He sees this as already happening. One of the hardest problems in integrating social sciences with the physical sciences is the tendency to ‘reduce’ social, economic or psychological phenomena into simplistic, sweeping, and hence often wrong as well as dangerous generalizations.

The most glaring examples are social-Darwinism along with many pop bio-psychological explanations which appear in popular magazines.

In this book, Capra provides that much-needed yet elusive connection between social sciences and other physical sciences in a non-reductionist framework that is more importantly also workable and can have practical applications in community welfare and sustainable development without compromising the freedom that a market economy provides. From the molecular communications networks slowly evolving in the proto-cells of the primeval ocean to the digital social networks connecting the planet, Capra charts out a path for sustainable development by bringing to notice connecting strands of life, cognition, nature and community which have hitherto gone unnoticed.

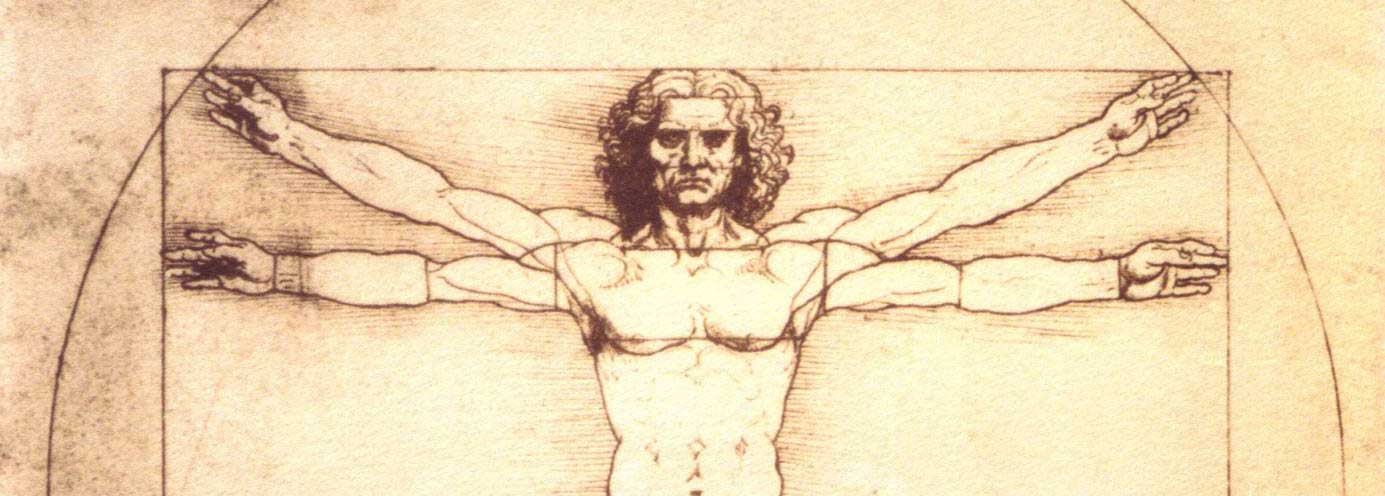

TO SCIENCE THROUGH ART: DA VINCI AS SYSTEMS THINKER

The next two books review the science of Leonardo da Vinci and the relevance of his science to the present evolution of systems science. Leonardo was known more as an artist and technological innovator than as a scientist. For Capra, Leonardo arrived at science through art and that makes all the difference. Thus he avoided the pitfalls of reductionism we encounter in Newton, Galileo and Bacon. In ‘The Science of Leonardo’ (2007), Capra reveals many interesting dimensions of Leonardo’s worldview that far exceeded his own time. He was the first systems thinker according to Capra. Leonardo envisioned rivers as almost beings with life. In planning any city, he would make the river an integral part of the city landscape – almost a biological integration. He was asked to build Cathedrals and he designed “temples”. His architecture, his town planning, and his view of nature – all these emerged from his holistic understanding of nature. Capra shares how he arrived at this vision of Leonardo da Vinci:

As I gazed at those magnificent drawings juxtaposing, often on the same page, architecture and human anatomy, turbulent water and turbulent air, water vortices, the flow of human hair and the growth patterns of grasses, I realized that Leonardo's systematic studies of living and nonliving forms amounted to a science of quality and wholeness that was fundamentally different from the mechanistic science of Galileo and Newton (Preface, XVIII).

Europe unfortunately never adapted Leonardo’s ideas for city planning. However, centuries later another European, a Scot, would discover a similar organic city planning in another civilization.

Capra sees in the painter of The Last Supper “a systemic thinker, ecologist, and complexity theorist; a scientist and artist with a deep reverence for all life, and as a man with a strong desire to work for the benefit of humanity.” Clearly in the centuries that followed Leonardo, the science he envisioned was lost to the science of Newton, Bacon and Descartes. One interesting aspect of Leonardo is his novel approach to city planning. Capra points out:

It is clear from Leonardo’s notes that he saw the city as a kind of living organism in which people, material goods, food, water, and waste needed to move and flow with ease for the city to remain healthy (p. 58).

Europe unfortunately never adapted Leonardo’s ideas for city planning. However, centuries later another European, a Scot, would discover a similar organic city planning in another civilization. In the planning of the temple cities of South India, Patrick Geddes saw an integration of the social life and cultural life cycle of the people that was unheard of in the West. According to Leonardo, if one wants to change the course of a river for human purposes then it should be done gently through such sustainable technologies like small dams. He wrote: “A river, to be diverted from one place to another, should be coaxed and not coerced with violence” (p. 263).

In the planning of the temple cities of South India, Patrick Geddes saw an integration of the social life and cultural life cycle of the people that was unheard of in the West.

An Indian mind cannot but remember the legend of young Sankara singing and appealing the Purna River to change its course. Buried in this legend of Sankara is perhaps a poetic invitation for the science of sustainable water management.

In Learning from Leonardo (2013) Capra studies the notebooks of Leonardo, and the book provides a new approach to the history of science. With a detailed timeline of milestones in science from the time of Leonardo (16th century) onwards into twentieth century, Capra purports to show how the artist anticipated or even independently discovered many of the later developments of science. According to Capra, Leonardo developed an empirical method. The Church that considered Aristotelian philosophy its theological bedrock viewed experimental science with suspicion. But da Vinci broke with that tradition. Capra claims:

According to Capra, Leonardo developed an empirical method. The Church that considered Aristotelian philosophy its theological bedrock viewed experimental science with suspicion. But da Vinci broke with that tradition.

One hundred years before Galileo Galilei and Francis Bacon, Leonardo single-handedly developed a new empirical approach to science, involving the systematic observation of nature, logical reasoning, and some mathematical formulations— the main characteristics of what is known today as the scientific method (p. 5).

In almost every field from mechanics to ecology – some of these disciplines not even imagined at his time - Leonardo through observation, experimentation and contemplation- had made a remarkable addition to human knowledge. For example, Capra points out:

“Leonardo did not pursue science and engineering to dominate nature, as Francis Bacon would advocate a century later.”

Leonardo understood that these cycles of growth, decay, and renewal are linked to the cycles of life and death of individual organisms: Our life is made by the death of others. In dead matter insensible life remains, which, reunited to the stomachs of living beings, resumes sensual and intellectual life. . . . Man and the animals are really the passage and conduit of food (p. 282).

This remarkable insight according to Capra anticipates the concept of food chains and food cycles that was developed by Charles Elton almost four centuries later in 1927. Finally Capra distinguishes the basic difference between the science of Leonardo and the science of Francis Bacon: “Leonardo did not pursue science and engineering to dominate nature, as Francis Bacon would advocate a century later.” Leonardo had a ‘deep respect for life, a special compassion for animals, and great awe and reverence for nature’s complexity and abundance.’ If this assessment of Leonardo by Capra makes the artist sound like a Jain born in late medieval Italy, check this statement by Leonardo himself “One who does not respect life does not deserve it.” Does it not reflect the Jain dictum, ‘Live and let live?’

A LIFE IN HOLISTIC DIALOGUE

The most recent work of Dr. Capra is ‘A Systems View of Life – A Unified Vision,’ coauthored with biochemist Pier Luigi Luisi. Published by Cambridge University Press in 2014, the book is intended to serve as a text book for students as well as the general reader who want to study sustainable development integrating the physical, biological, cognitive, ecological, and social dimensions. In the first part Capra explores the rise of mechanistic world-view and in the second part the emergence of systems thinking. The third part studies the new concept of life and the fourth is about sustaining the web of life even as human societies develop. The book is actually the encapsulation of the entire pilgrimage of exploration that Capra undertook from the dance of Siva to the drawings of Leonardo. The book is of immense relevance to India, a developing nation with rural communities that are almost lost in the era of globalization with a skewed playing field.

The book is actually the encapsulation of the entire pilgrimage of exploration that Capra undertook from the dance of Siva to the drawings of Leonardo.

The book is of immense relevance to India, a developing nation with rural communities that are almost lost in the era of globalization with a skewed playing field.

The book is of immense relevance to India, a developing nation with rural communities that are almost lost in the era of globalization with a skewed playing field.

With eco-conflicts set to escalate in the future and divisive forces try to exploit them in both sides of the left-right fence, the worldview of Capra provides a holistic alternative. Preservation of local knowledge systems, creating networks of green innovators and eco-entrepreneurs at the local level and globally networking them – all these are possibilities envisioned in Capra’s worldview. While most leftwing eco-militants devalue local spiritual and cultural elements, Capra has also brought out a powerful reading of the Eastern spiritual symbols in the light of modern science. For sustainable development, we ultimately need a drastic change in the educational system. Capra, though not explicitly or perhaps even intentionally, has provided a Dharmic framework, or at least has sown the seeds for developing a broader inter-disciplinary science of sustainable development with a Dharmic framework. Using his pioneering works spanning a lifetime, each native culture and tradition can chart out a spiritual, holistic pathway to sustainable development. After all, the native traditions which are struggling for their very survival on a planet dominated and to a significant extent devastated by the supremacy and expansionism of Abrahamic values, can now knowledge-network themselves with mutual spiritual validation to become important vehicles for the sustainable development and preservation of the web of life. In this they may even transform the expansionist and monocultural tendencies in the Abrahamic value system.

Links: http://www.sutrajournal.com/fritjof-capra-and-the-dharmic-worldview-aravindan-neelakandan